All my course assessments are created using PrairieLearn, an online problem-driven learning system that enables the creation of problem generators. These problem generators are designed to produce unique problem instances with varying numeric values or other modifications, ensuring that the correct answer differs across attempts. Most problems are auto-graded and provide immediate feedback, providing the following benefits: a) students can get immediate feedback about their knowledge, and adjust their studying accordingly, b) grading is more consistent among all the students, which is specially difficult when grading more than 200 assignments, c) course staff is not spending a huge amount of time grading papers that are often not collected, and instead can focus on creating better course content and experiment with innovations in the classroom.

Homework and exams assigned in PrairieLearn consist of a set of problem generators, which include both non-coding and coding questions. The grading methods and retry options for these assessments vary and are summarized below:

Homework assignments:

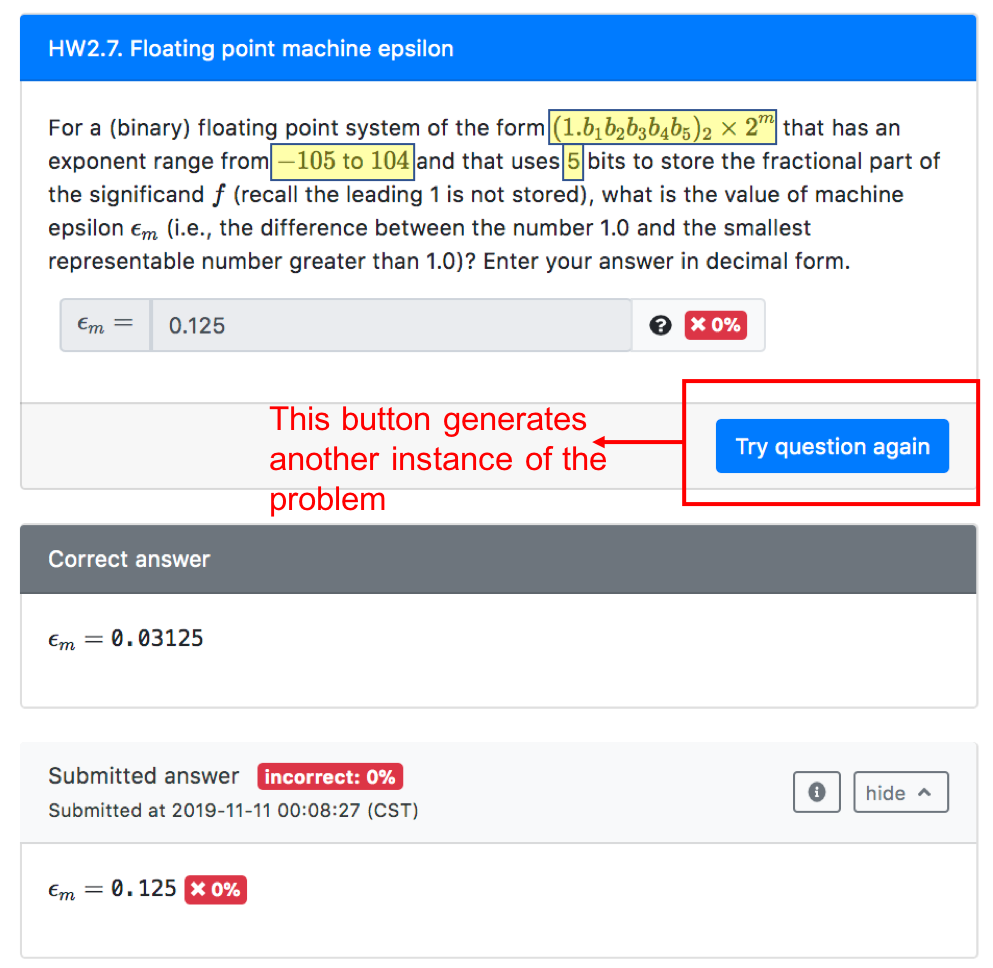

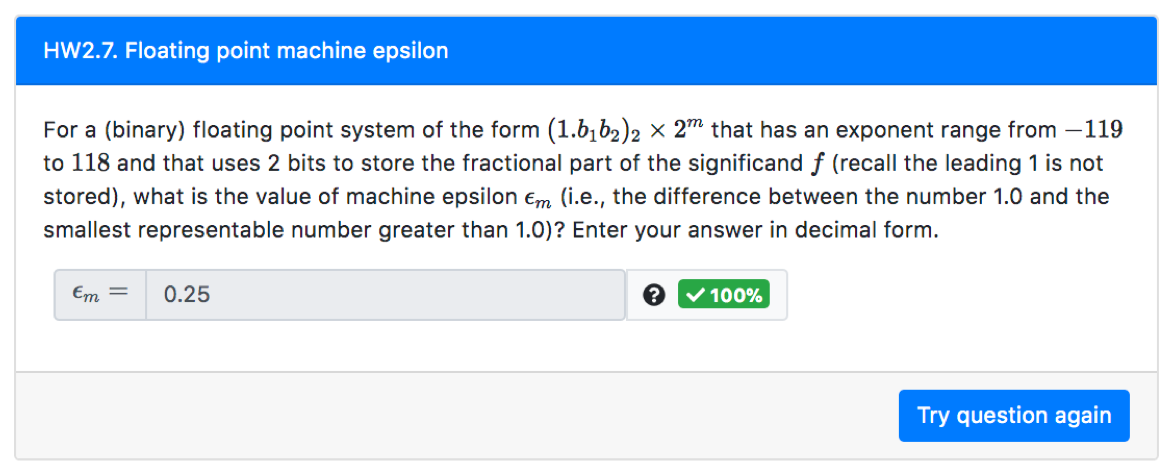

A typical problem generator will have parameters that are randomized, creating different problem instances. Figure 1 illustrates a question from a problem generator in which the highlighted variables were parametrized.

In a homework assignment, if a student gets a question marked as incorrect (Fig. 2), the correct answer is displayed and the student cannot submit another answer for the same problem instance. Instead, students can attempt another instance by clicking “Try question again”, as illustrated in Fig. 3.

Students can still generate other instances after the question is marked as correct, as shown in Fig. 3. To encourage students to practice with more than one version of the question, I often give students points for answering the question correctly more than once. If the question is not fully randomized (as in the case with some multiple-choice questions), then I don’t show the correct answer after each attempt, and they only get points for correctness once.

Exams and/or short quizzes:

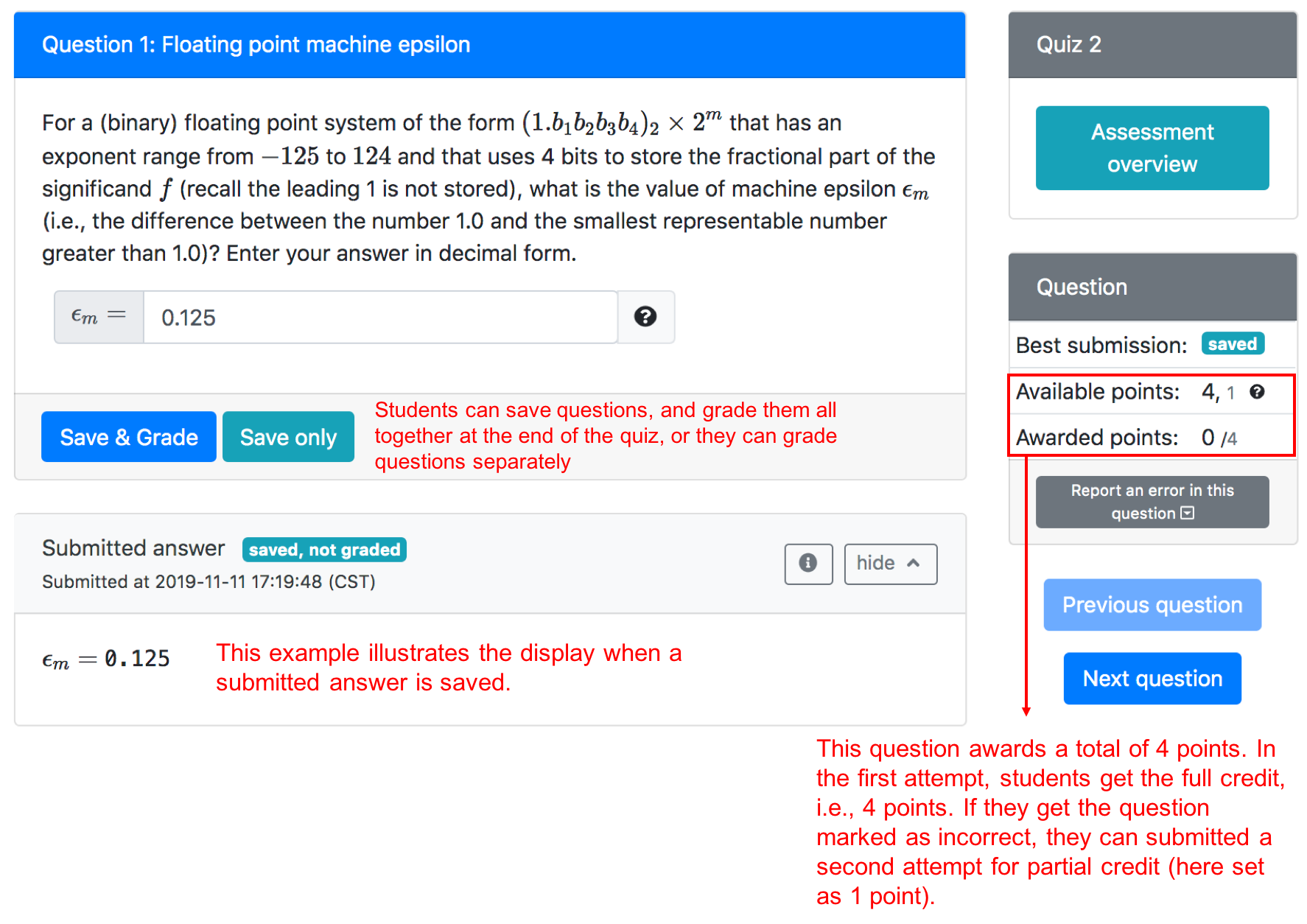

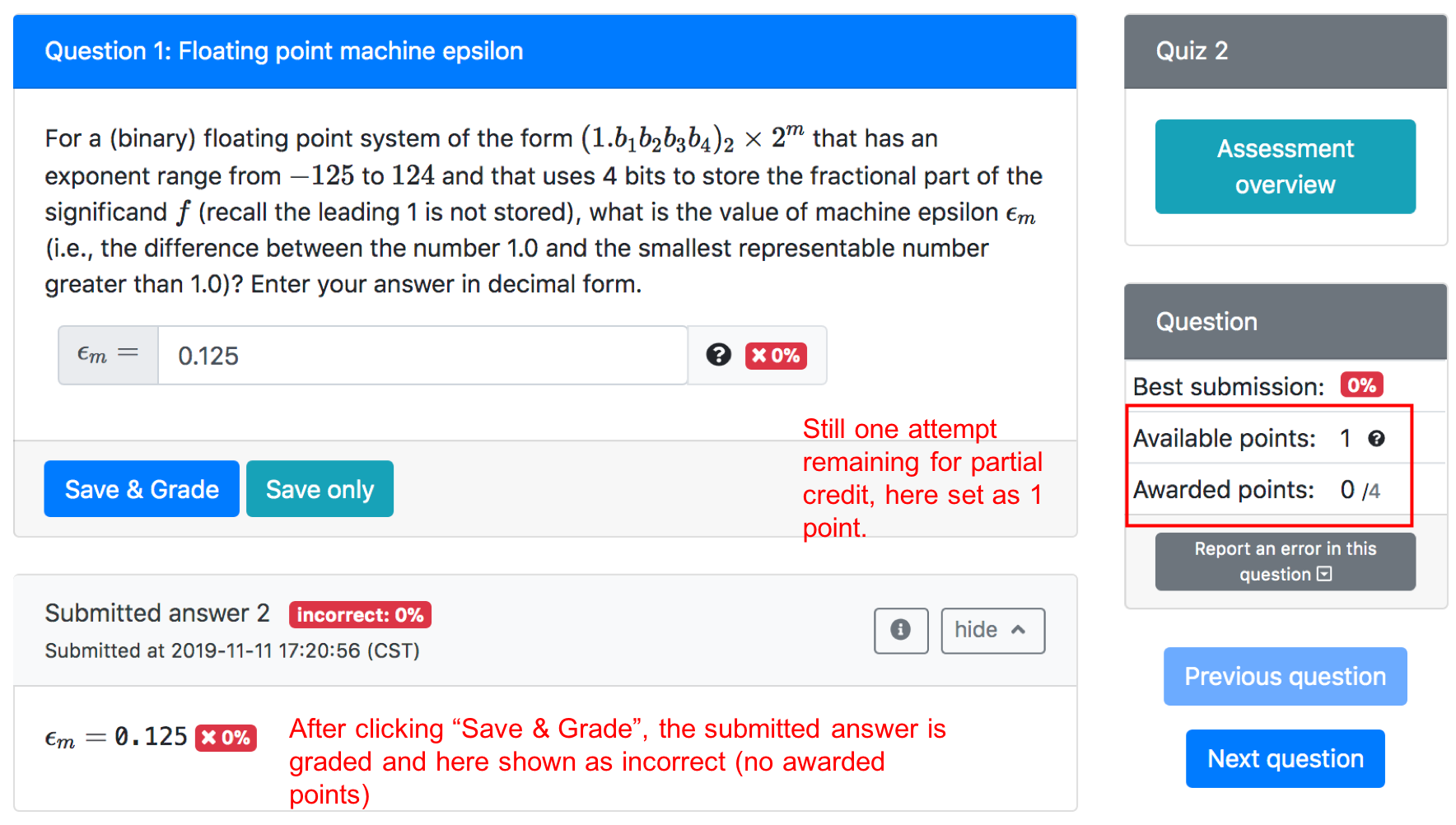

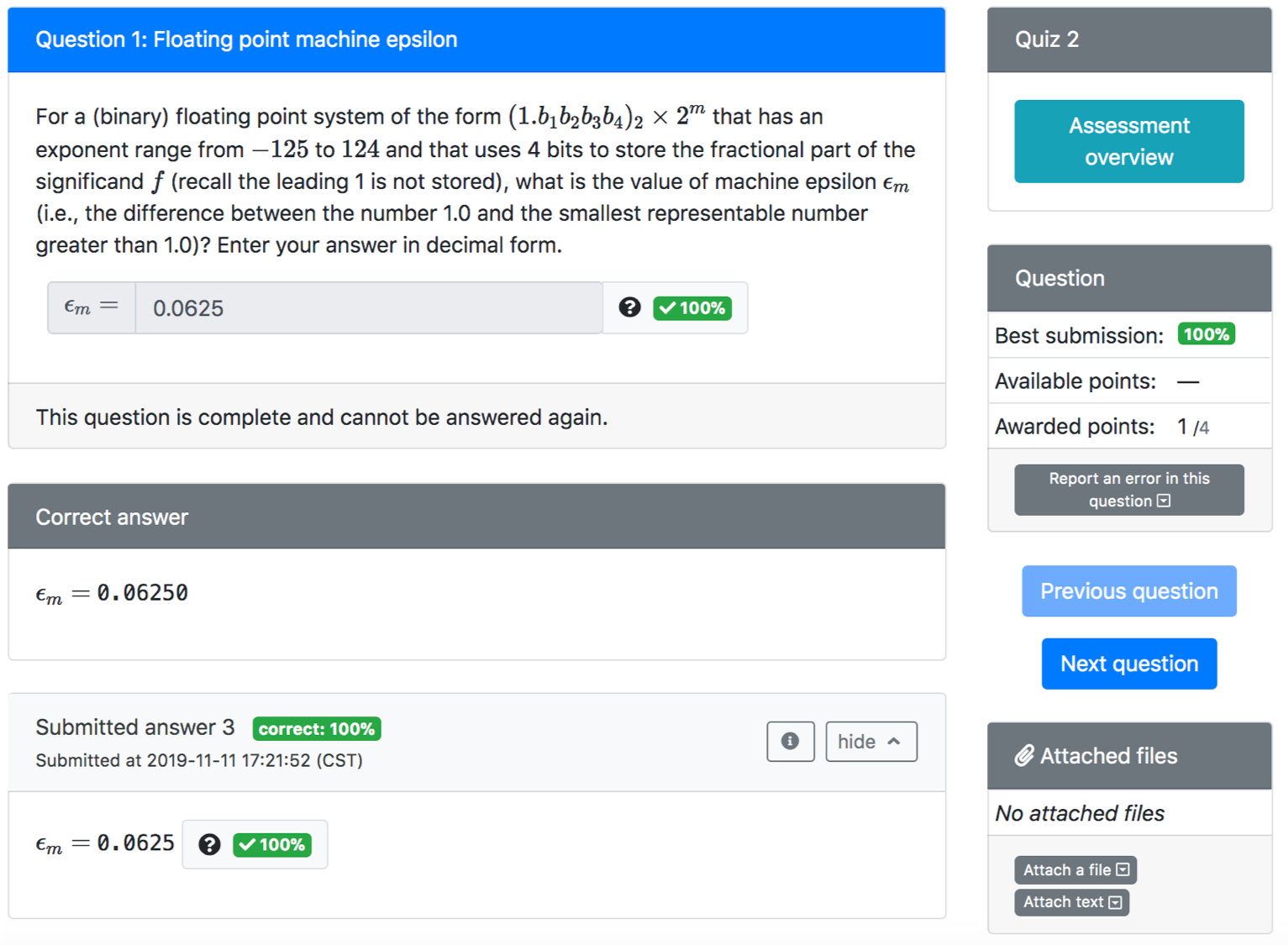

The same problem generator included in an exam will have a different behavior when creating problem instances. Figure 4-6 illustrate another instance of the same problem appearing on a quiz. In this question, students have two attempts to get the question correctly. A student who has an incorrect submission in the first attempt can try the same question again (and not another instance) for a reduced amount of points.