Non-coding questions appear in homework and quizzes. In the courses I teach, they mostly appear in the form of numerical or matrix input, and multiple-choice and checkbox formats. The grading of these questions will vary, depending if they are included in a quiz or HW. In HW assessments, students have unlimited attempts to get the question marked as correct, and can get variants of the same question for practice. In quizzes, students receive only one variant of the question, and may have more than one attempt for partial credit (read more about assessment formats here).

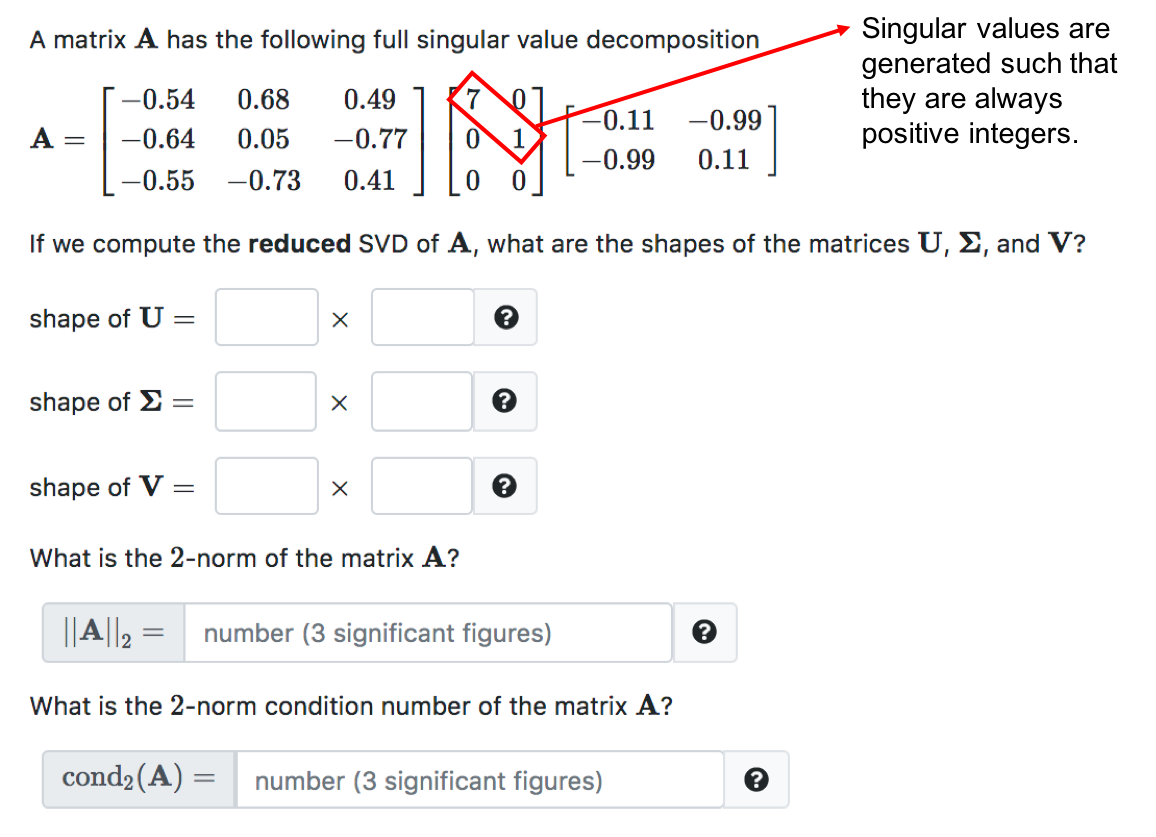

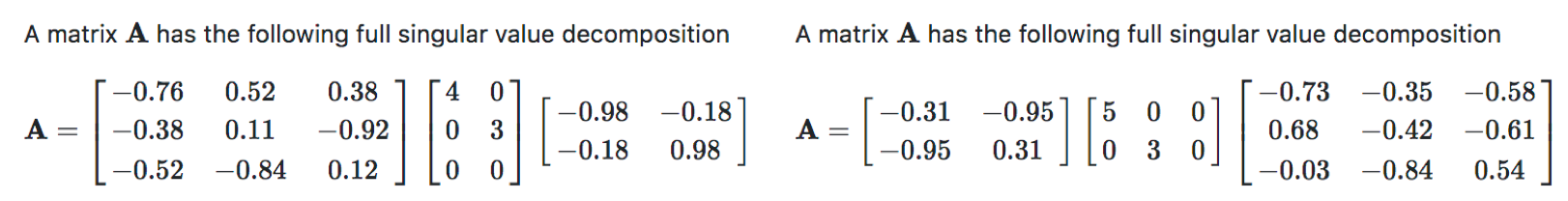

Example 1: question with numerical input fields

Figure 1 illustrates a typical HW question, where students can answer a series of small questions regarding the same problem. This question generates the matrix A in a carefully randomized way, making sure all the singular values are always positive (to guarantee full rank) and that they are given by integer numbers (for simplicity of the calculations). Students that have mastered the concepts about SVD are able to answer this question without any special computation. However, students that are still in the process of learning these concepts may be using other resources to actually compute the required quantities. When this question is included in a HW, students can generate different versions of the same question, where the matrix A can have different shape and values, as illustrated in Fig. 2.

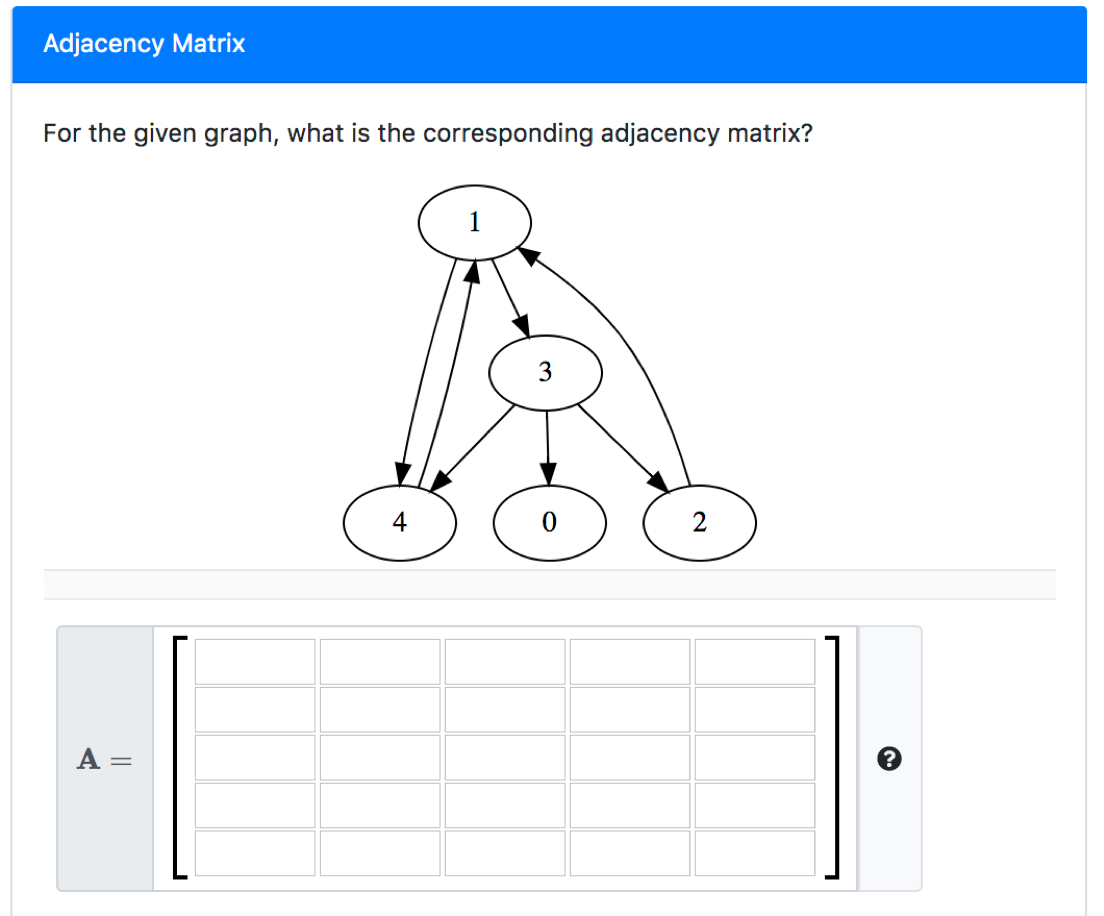

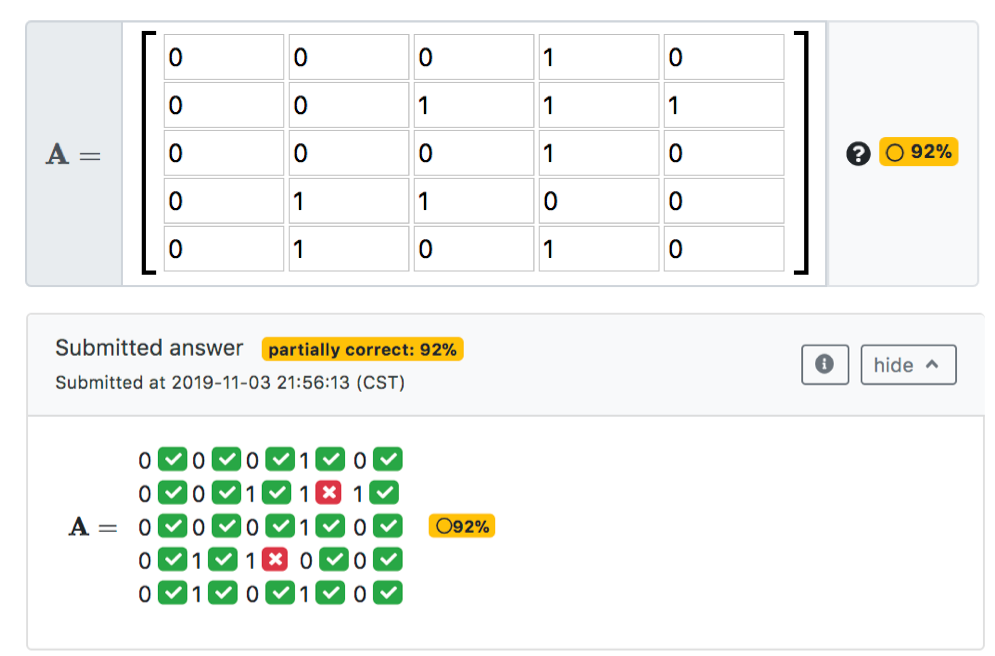

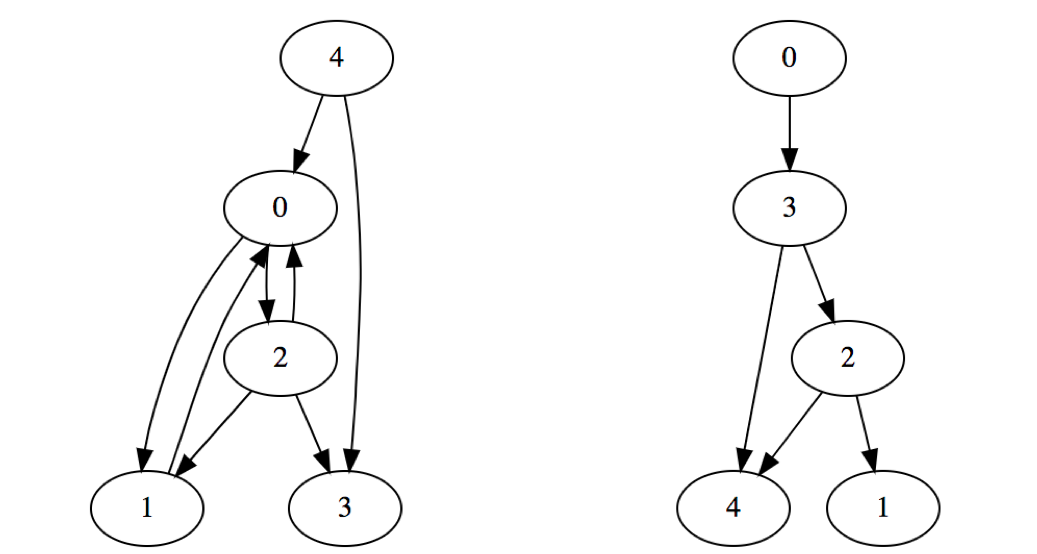

Example 2: question with matrix input fields

Figure 3 shows an example where students need to provide a matrix as the answer to the question. Here each entry of the matrix receives partial credit, as illustrated in Fig. 4. Questions authors also have the option to set the question as “all-or-nothing”. The graph is generated at random, and hence students receive different variants of the question, as shown in Fig. 5.

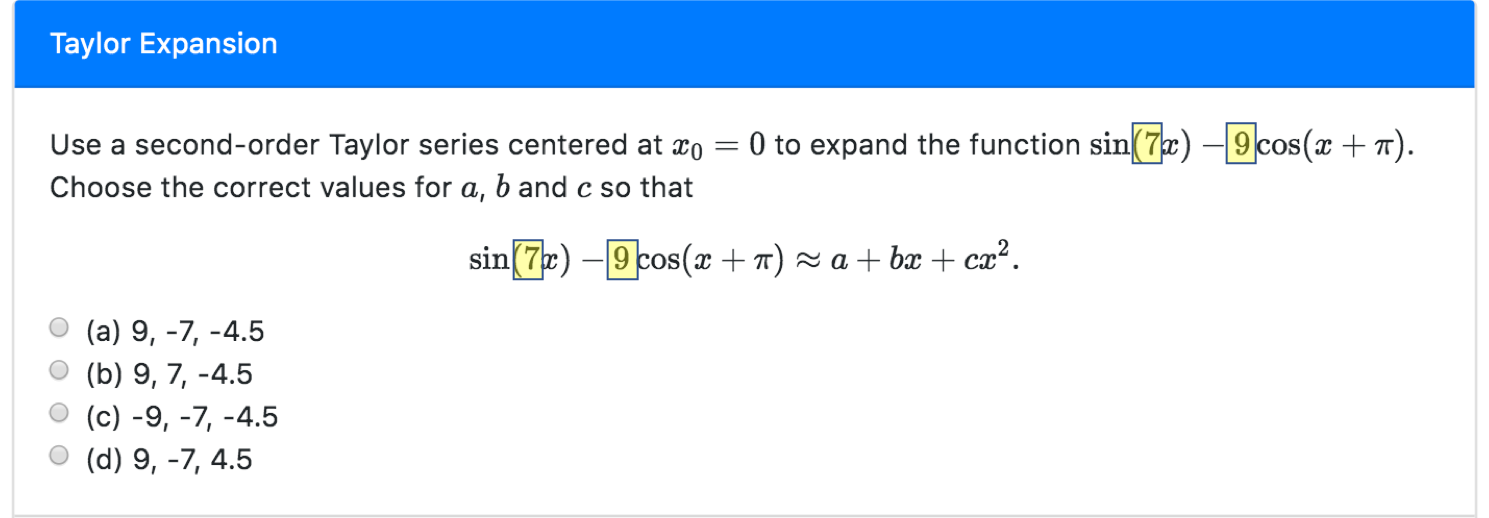

Example 3: question with multiple-choice

This example illustrates a multiple-choice question that has parameterized options. The highlighted parameters are generated at random, and the set of distractors and correct answer are generated based on these parameters (Fig. 6).